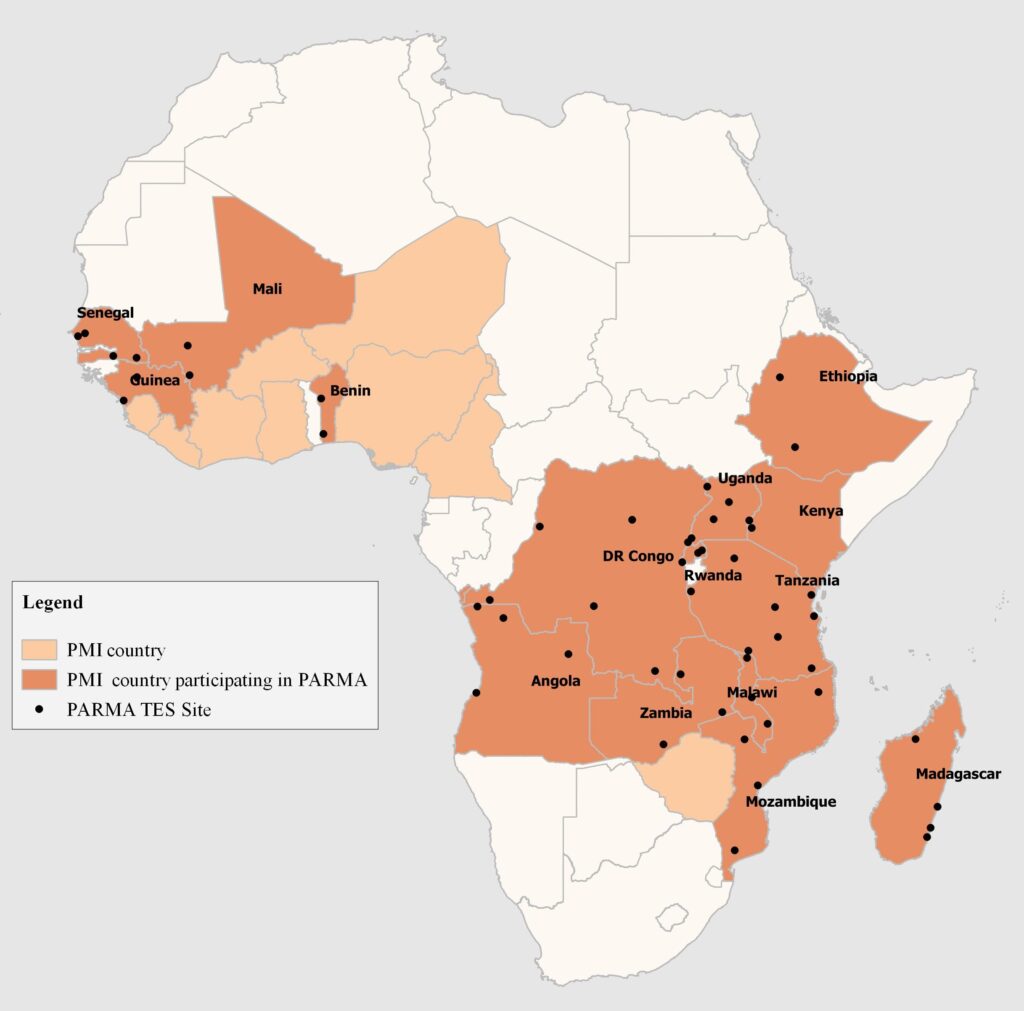

Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) treat millions of malaria cases quickly and cheaply. Yet—if drug-resistant malaria is left unchecked—we risk losing this lifesaving medicine. Tracking genetic markers of resistance can show when and where action is needed to stop resistance from spreading—and keep ACTs working. The U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI)-supported Antimalarial Resistance Monitoring in Africa (PARMA) Network is facilitating this fight.

Therapeutic efficacy studies tell us if patients are responding to malaria treatments, but not why. Testing samples collected from these studies for genetic markers of drug resistance can help explain treatment failure at the molecular level and inform recommendations for treating malaria worldwide. Yet, not many countries have the capacity to conduct this genetic testing, either outsourcing this or foregoing it altogether. PARMA trains local scientists in PMI countries to perform these tests independently and self-monitor resistance.

Data generated by this training will allow my country to have a good map of the resistance to antimalarials…All we have learned will allow us to implement a molecular surveillance system across the DRC. — Dr. Papy Mandoko, participant from the Democratic Republic of the Congo

PARMA trains visiting African scientists over six to eight weeks at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) malaria laboratory in Atlanta. Trainees acquire a host of laboratory skills, including photo-induced electron transfer PCR, Taqman based real-time PCR, and Sanger sequencing. The results generated from these tests are complex, but trainees also learn bioinformatics to analyze their findings and have opportunities to enhance presentation and writing skills.

Senegal, Tanzania, and Mali show PARMA’s mission is achievable. With training support, laboratories in these countries are applying advanced molecular techniques to monitor resistance to antimalarials.

During visits to CDC, we were trained and acquired skills for detection of markers of drug resistance…The strategy adopted and used by PARMA of “See one, do one, teach one” is excellent and pertinent to our long term goal of acquiring and transferring important technologies to the laboratories in malaria endemic countries in Africa…Our future goal is to ensure the methods are working well and to offer training to colleagues from other countries in Eastern and Southern Africa. —

PARMA has now trained 14 scientists from 10 countries, including two Rwandan scientists who graduated from the program in December 2018. At least four more countries plan on sending trainees in 2019.

We will no longer send samples to an external laboratory for analysis…We are so grateful that PARMA helped us to grow into our potential.

Countries cite multiple benefits of participating in PARMA, including lower costs and faster processing from conducting tests in house. Once countries possess antimalarial resistance results, they are encouraged to share these with the World Health Organization, Worldwide Antimalarial Resistance Network, and other organizations that map global antimalarial resistance. Monitoring antimalarial resistance is a global effort. So far, results generated from PARMA collaborations have provided reassurance that ACTs in Africa remain effective. Unlike Southeast Asia, where resistance has compromised use of this vital medicine, mutations associated with resistance have not yet been detected in PARMA-evaluated samples from Africa. When resistance does emerge, PARMA-supported countries will be ready to respond.

Cover image: Recent trainees from Rwanda with a PARMA trainer. From left to right: Zhiyong (Jane) Zhou, Tharcisse Munyaneza (back), and Madjidi Rafiki (at hood).