The extremely successful global healthcare program sets malaria eradication goals in some countries

In an era when partisan squabbling threatens to bring the U.S. government to a halt, one of America’s most successful global health programs, begun under President George W. Bush in 2005, is about to enter a second phase. Known as the President’s Malaria Initiative, or PMI, the program is considered by many to be one of the best run and most effective of the U.S.’s worldwide health efforts.

The initiative is one of the largest players in the international effort to combat malaria, which kills more than half a million people a year. An estimated 4.3 million fewer malaria deaths occurred between 2001 and 2013, according to the World Health Organization, which is about a 47 percent reduction in the number of deaths if malaria patterns in 2000 had gone unchecked.

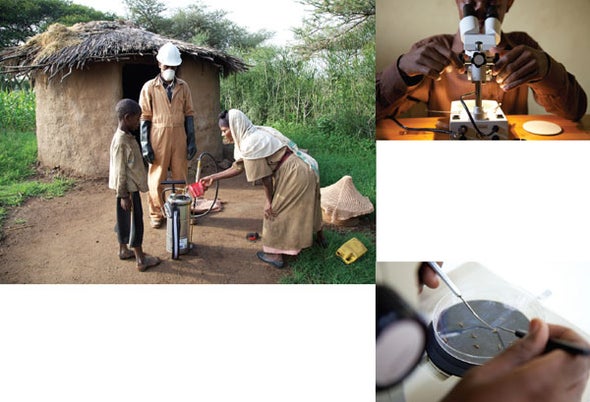

PMI accounted for a substantial part of this success. The program is based on four interventions: insecticide-treated mosquito nets, indoor spraying, testing and treatment with artemisinin-based drugs, and preventive treatment of pregnant women. The next phase of the strategy, under the Obama administration, will build on the gains, seeking to reduce malaria deaths by 30 percent between 2015 and 2020 in 19 target countries in sub-Saharan Africa and in the Greater Mekong region in Asia. (There were 198 million malaria cases globally in 2013.) Efforts will even aim to eliminate the disease in some countries. The program will also address drug and insecticide resistance to malaria, along with each country’s capacity for its own treatment, monitoring and surveillance.

The secret to the initiative’s success seems to be that it takes on mundane but often overlooked management issues that can trip up global health programs. PMI’s approach is holistic: it takes responsibility for every link in the chain, from procurement to quality control. U.S. global health officials in other fields say it is a model particularly for its sustained focus on a limited number of targeted interventions in countries with a high burden of disease.

The recent accomplishments of anti-malaria programs may have the unintended consequence of creating a sense of complacency at a time when efforts need to be amplified. Despite increases in the past decade, the overall global budget for malaria control is still projected to lag by more than $2 billion a year compared with what the mission requires, according to the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. And a new PMI strategy document warns of “waning country and donor attention” as malaria rates drop. At the launch of the second phase of the initiative at the White House in February, Bernard Nahlen, deputy coordinator, warned: “The minute you take your foot off the pedal, malaria will come back with a vengeance.”