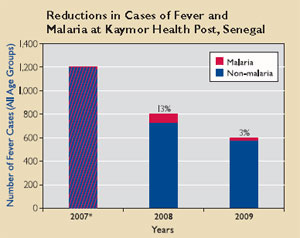

In 2007, the year that both indoor residual spraying (IRS) and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) were introduced in his community, about 30 percent of the fever cases that he saw were malaria.

Chief Nurse Arona Gueye stands outside of the Kaymor Health Post in Senegal, where malaria cases have declined with the increase in malaria prevention activities. Source: Matar Camara/PMI

“I tell you,” Arona comments, “it is clear now that IRS, combined with the ITNs we had already received, produced exceptional results. Malaria is backing down, and if this trend continues, the next generation of nurses will not be able to recognize a clinical severe malaria case.”

*Note about figure at right: In 2007, malaria cases were diagnosed on the basis of patients’ symptoms only, with no laboratory confirmation. About 30 percent of fever cases in 2007 were suspected malaria cases. At the end of 2007, rapid diagnostic tests were introduced, and malaria cases in 2008 and 2009 were confirmed using these tests.

*Note about figure at right: In 2007, malaria cases were diagnosed on the basis of patients’ symptoms only, with no laboratory confirmation. About 30 percent of fever cases in 2007 were suspected malaria cases. At the end of 2007, rapid diagnostic tests were introduced, and malaria cases in 2008 and 2009 were confirmed using these tests.