Sakda Wongwasana, a health worker at the Vector-Borne Disease Control Unit 7, Satun province, Thailand, uses a microscope to check the blood film of a suspected malaria patient. Credit: Permsak Tosawad, Inform Asia

Thailand has seen incredible progress against malaria over the past decade – with an 88 percent decline in malaria cases since 2012 and a 74.7 percent reduction in the number of villages with malaria transmission, the country is well on its way to reaching its goal of eliminating malaria by 2024.

However, Thailand faces a constant threat on its journey toward malaria elimination – resistance to the drugs used to treat malaria. Since the late 1950s, the Greater Mekong Subregion has been the epicenter of emerging resistance to malaria drugs, with resistance first detected along Thailand’s border with Cambodia and eventually spreading to many other countries. Even as countries have adjusted and developed new drugs, the malaria parasite continues to mutate and develop resistance to the latest front-line treatments, endangering global progress to date, posing a threat to global health security, and putting millions at risk.

The good news is that, with the support of the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and global partners, Thailand’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (DVBD) is coming up with new and innovative methods for early detection of drug resistance and response that serve as a beacon of hope in the fight against malaria.

To confront this challenge, the PMI-funded Inform Asia: USAID’s Health Research Program, implemented by RTI International, worked closely with the DVBD and the World Health Organization in 2017 to launch an integrated drug efficacy surveillance (iDES) system, which builds on Thailand’s long-standing efforts to monitor drug resistance.

Thailand is the first country to pilot and implement this approach, which incorporates drug resistance monitoring as part of routine malaria surveillance and response. It requires that every malaria patient receives treatment according to national guidelines and is followed up four times to ensure the treatment remains effective. The end goal? Every single person that gets malaria is treated, tracked, and cured.

Previously, drug resistance was monitored in fixed study sites that required research teams and at least 50 patients to participate. However, as the number of malaria cases continued to decline in Thailand, these studies struggled to recruit sufficient patients and adequate sample sizes for analyses. iDES was introduced to tackle this challenge.

As part of iDES, blood samples are collected at health facilities whenever a malaria patient is diagnosed and treated. Local laboratory teams use microscopic techniques to determine whether the malaria parasites are cleared from the patient’s blood during and after treatment. If they still detect parasites on any follow-up date, the parasite could be developing resistance to the treatment the patient received.

Using this follow-up method, the national malaria program can capture and monitor data on drug efficacy from across the country as patients are routinely treated and diagnosed, as opposed to having limited data in only certain areas – a big win for being able to quickly identify and halt the spread of drug-resistant malaria in its tracks.

However, there are limits to what the lab results can tell us about drug resistance. If a test comes back positive, it could be due to several factors – the patient may not have taken the medicine properly, the medicine may not have been up to par, or the strain of malaria they have could be resistant.

Dr. Aungkana Saejeng, head of the Division of Vector-Borne Disease Laboratory, Thailand Ministry of Public Health, explains the process of iDES to her staff in Nonthaburi, Thailand. Credit: Permsak Tosawad, Inform Asia

Dr. Aungkana Saejeng has worked for more than 20 years to combat malaria in her country, and currently serves as the Chief Medical Technologist at DVBD’s national lab outside of Bangkok, where she leads a team of scientists devoted to studying and monitoring drug-resistant malaria. Her national lab is responsible for conducting more specialized tests on a portion of the blood samples from across the country as both quality assurance for health facilities and to provide a better understanding of drug resistance trends.

She describes some of the challenges in ensuring the standards of iDES are met to collect and interpret drug resistance trends.

“One of the main challenges in monitoring antimalarial drug resistance is incomplete drug compliance,” says Dr. Saejeng. “Many malaria patients live in remote areas and have a difficult time traveling to the hospital for treatment and follow-up. Reaching these patients to ensure they take all of their medicine and their blood is tested is essential in obtaining the most accurate data we possibly can.”

Reaching the Unreachable

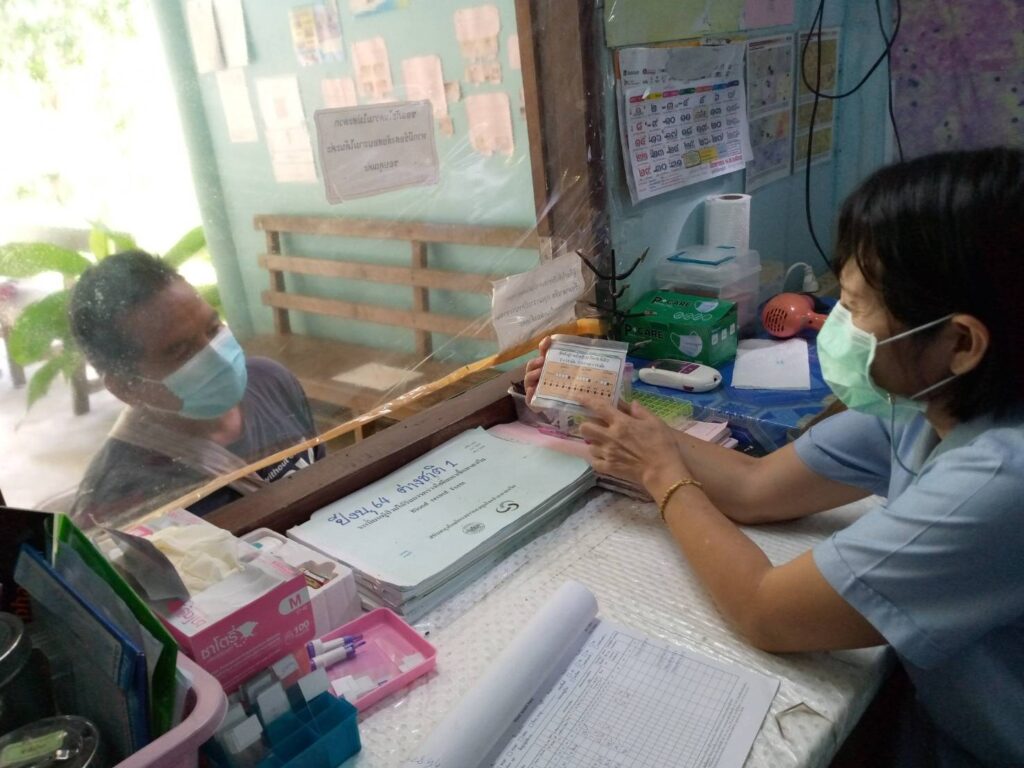

A health worker at the malaria clinic in Mae Hong Son Province, Thailand, explains to a malaria patient how to take malaria medicine following the guidelines on the medicine bag. Credit: Vector-Borne Disease Control Unit 1.1.2

Treatment for Plasmodium vivax malaria, the most common type in Thailand, requires 14 days of medication, which can be hard for malaria patients to remember. It presents a particular challenge for those who live in remote villages and may not have regular access to a health worker or health facility. Dr. Nardlada Khantikul, a Senior Public Health Technical Officer at the Office of Disease Prevention and Control based in Chiang Mai, developed a tool to make it easier for hard-to-reach patients to take their complete course of medicine.

Dr. Khantikul created a sticker to go on medicine packs with bubbles for the patient to check off once they’ve taken each required dose. Though it may seem simple, this serves as a clear reminder for patients to take their medicine correctly – important both for becoming fully cured and improving the accuracy of drug efficacy data.

Community health workers are also an integral part of the continuous follow-up with patients that is a hallmark of Thailand’s integrated surveillance system and essential in reaching the unreachable.

For Chokchai Phichitpatapee, follow-ups from a health worker were what led him to being cured of malaria. Chokchai grew up in a small remote village in the Mae Sariang District in northwestern Thailand, where it was not uncommon for people to fall ill and die from malaria because they were unable to reach the hospital for treatment.

After working for many years as a security guard in Bangkok, he returned to his village to take care of his parents and joined a squad of park rangers at Salween National Park. Chokchai and his team patrolled the park both day and night, at times needing to spend the night in the forest. Sometimes he forgot to bring a mosquito net or apply mosquito repellent, so he became infected with malaria twice. Each time, health workers from Mae Sariang Malaria Clinic diagnosed and treated him, following up four times to take blood samples and checking the stickers on his medicine pack to ensure he took the complete course of medicine. In addition to testing Chokchai and his team, the health workers also took blood samples from villagers surrounding the park to make sure that any additional malaria cases in the area were detected.

Park ranger Chokchai Phichitpatapee relaxes on his hammock, after staying overnight in the forest during a long-range patrol mission. Credit: Courtesy photo. Credit: Courtesy photos

“We didn’t know that malaria medicine needs to be taken completely even if symptoms are gone,” said Chokchai. “If the malaria worker had not followed up with me and the people around here, we would not have been cured.”

A Strong Surveillance System is Key

Thai health workers cross-check the data in the integrated drug efficacy surveillance (iDES) system to ensure accuracy. Credit: Permsak Tosawad, Inform Asia

Thailand’s comprehensive case-based surveillance system, which allows malaria officers to quickly detect and respond to individual cases across the country, is the backbone of efforts to combat drug resistance and eliminate malaria. It also supports a resilient health system that can quickly detect and respond to infectious disease threats beyond malaria, like COVID-19. iDES, however, is only possible when there are a low enough number of cases, sufficient capacity to monitor and analyze data, and a robust surveillance and response system to enable complete follow-up.

PMI has been a key partner in Thailand’s journey to strengthen its surveillance system and move towards malaria elimination. Inform Asia has leveraged its expertise in information technology and epidemiology to support the national malaria program in collating patient data into a single national database, Malaria Online, where health workers from the national to village level can access information that they need for targeted response. It has also supported the launch of the 1-3-7 surveillance strategy, which helps ensure that every single malaria case triggers a whole set of actions to prevent outbreaks.

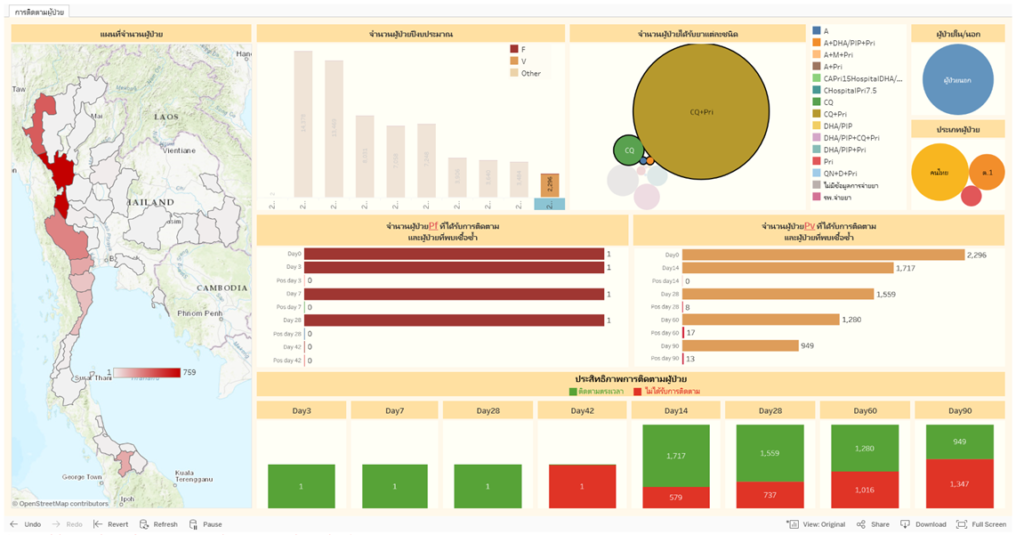

The program has also worked with DVBD to design new web-based analytics and interactive dashboards that make it easier to interpret the wealth of information at decision-makers’ fingertips.

Most recently, this support has included the creation of new data visualizations for drug resistance monitoring. Previously, when a patient came into a health facility and was diagnosed and treated, data was captured in Malaria Online, where all routine data on malaria cases are captured. However, the lab results from drug resistance monitoring for that same patient were stored in a separate database, making it difficult to analyze the data.

Now, Inform Asia is working with national surveillance and laboratory teams to merge the drug resistance data into Malaria Online and create user-friendly interfaces so that malaria officers can more quickly identify which provinces or regions might be experiencing drug resistance. With these improvements, even health workers with limited data analysis skills can easily access and interpret trends in their specific region without having to sort through tons of data.

“With support from PMI and Inform Asia, lab and surveillance teams will be able to easily view and track drug resistance in addition to patient data, which will strengthen iDES monitoring for Thailand and the region,” said Saejeng.

From Dashboards to Policy

Recently, Thailand was able to use its wealth of surveillance data to develop evidence-based policy.

Between 2018 and 2019, Inform Asia and the DVBD found that Sisaket and Ubon Ratchathani provinces (located in Eastern Thailand) accounted for just 14 percent of the deadliest strain of malaria cases but 67 percent of treatment failures. This analysis led the DVBD to change the recommended treatment in these provinces and patients started receiving the new drug in 2020.

Going forward, Inform Asia continues to partner with the DVBD to improve the quality and completeness of drug resistance data, simplify and harmonize processes, and train public health staff on how to use and take full ownership of the system – ensuring they have the tools they need to carry their country across the elimination finish line.

Dr. Saejeng believes iDES can serve as a sustainable drug resistance monitoring model for other countries nearing elimination.

“I am proud of the work we have done to study and contain the spread of drug-resistant malaria in my country, and hope that others can learn from our experience. Nobody should have to die from this treatable disease.”