Close monitoring and analysis of malaria cases demonstrated that active surveillance at specific sites can allow the Government’s health system and its partners to detect epidemics early and respond quickly.

A laboratory technician records data in the Asendabo Epidemic Detection Site in Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Source: Addis Continental Institute of Public Health

Malaria transmission in Ethiopia is unique. Unlike other sub-Saharan African countries, in Ethiopia, malaria transmission varies greatly from year to year, with 75 percent of the country vulnerable to epidemics. Historically, epidemics tended to occur frequently, with large-scale epidemics flaring up every 5 to 8 years. And because the transmission pattern of the disease is variable, immunity is low, so everyone is at risk of infection, not just young children and pregnant women, which is the case in most other countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Another unique factor in malaria transmission in Ethiopia is that while the majority of malaria infections are due to the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, a second species, P. vivax, is found in up to 40 percent of all cases. This is important because artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are the recommended first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in most malaria-affected regions in Africa. But chloroquine, which is much less expensive than ACTs, can still be used to treat P. vivax.

Given all these factors, surveillance of malaria cases in Ethiopia is critical for early detection and response to epidemics. Therefore, the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), along with the Government of Ethiopia, supports 10 epidemic detection sites in Oromia Regional State. The goals of these sites are to detect, at the community and sub-community level, increases in malaria cases and epidemic outbreaks; pilot approaches in documenting the process prospectively; and respond to outbreaks in a timely and effective manner.

Through PMI’s implementing partner, Tulane University/Addis Continental Institute of Public Health (MEASURE III Project), malaria morbidity and operational program data are being collected continuously at the 10 health centers and their satellite community-level health posts. These sites serve around 366,000 residents. Since April 2010, 120,000 outpatient visits have been tracked; 33,000 of these patients were tested for malaria, and 8,800 were found to be infected with malaria parasites.

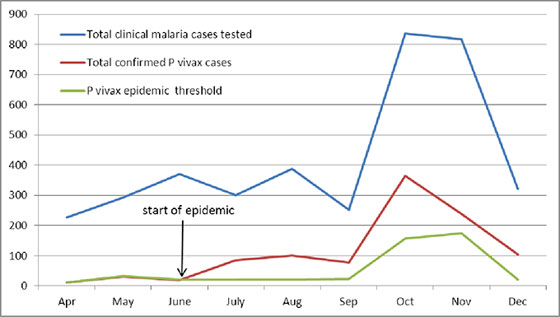

To date, the epidemic detection sites have detected three outbreaks of malaria, two due to P. falciparum and one to P. vivax. In Tullu Bollo Woreda, a dramatic increase in P. vivax cases was detected in October 2010. This triggered an immediate verification by diagnostic laboratory procedures, followed by notification of appropriate authorities and partners. In response, the Government expanded its education and communication activities, focusing on increased use of bed nets and prompt use of the health system for diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

By the end of October, the number of malaria cases had begun to fall; by December, cases had returned to typical levels for the health center in Tullu Bollo Woreda.

Close monitoring and analysis of malaria cases demonstrated that active surveillance at specific sites can allow the Government’s health system and its partners to detect epidemics early and respond quickly. A rapid response can help prevent epidemics from expanding to a larger geographical area and from potentially becoming unmanageable.

To allow for a more rapid detection of such events in the future, the MEASURE III Project is currently piloting an SMS (Short Message Service)-based system for data transmission.